Leaving Substack

MP 85: I'll be moving to Ghost next week, because it's a better fit for Mostly Python.

I’ve enjoyed writing Mostly Python over the past year, and plan to continue the newsletter indefinitely. I really enjoy a mix of working on various projects, writing about aspects of those projects that might be of interest to others, and exploring many aspects of Python itself in depth.

As much as I’ve enjoyed writing about Python and other technical topics, I’ve grown quite dissatisfied with Substack as a hosting platform. Starting next week, I’ll be using Ghost as a hosting service. The content of this newsletter won’t be changing, but the look and feel will be a little different.

In this post I’ll share some of the reasoning behind this change. I’ll also share some thoughts about how this relates to the choices programmers have to make about the platforms and services we rely on for many real-world projects.

What’s wrong with Substack?

I started using Substack because I was looking for a simple newsletter platform that would let me focus on writing. That’s what Substack was in its original form, but now they seem to be focusing on growth for growth’s sake. They also seem to be evolving into a social media platform that thrives on the kind of conflicts and divisiveness that has driven people away from other platforms.1

I just want to write a good technical newsletter, and Substack is no longer the most appropriate platform on which to do that.

Why Ghost?

If you haven’t heard of it, Ghost is a platform similar to what Substack was when it started. Just like with Substack, you can write a newsletter that becomes an online archive. You can write posts that go out over email, and others that are only available online. Ghost has been around for over ten years, and hasn’t tried to implement the kinds of social features that Substack has.

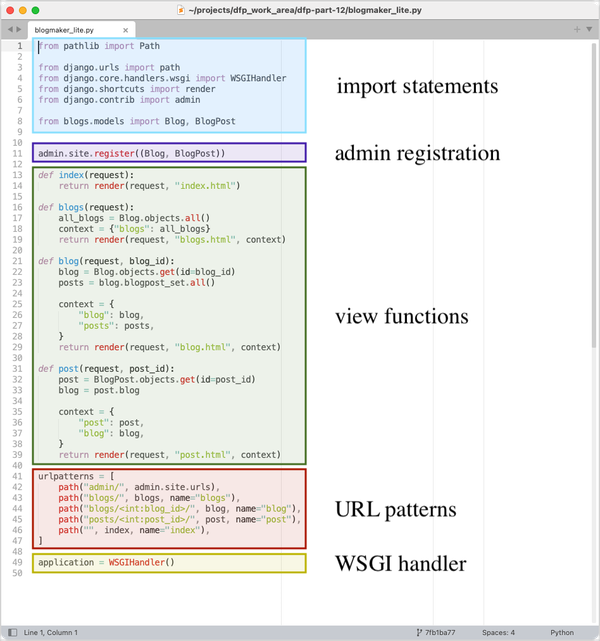

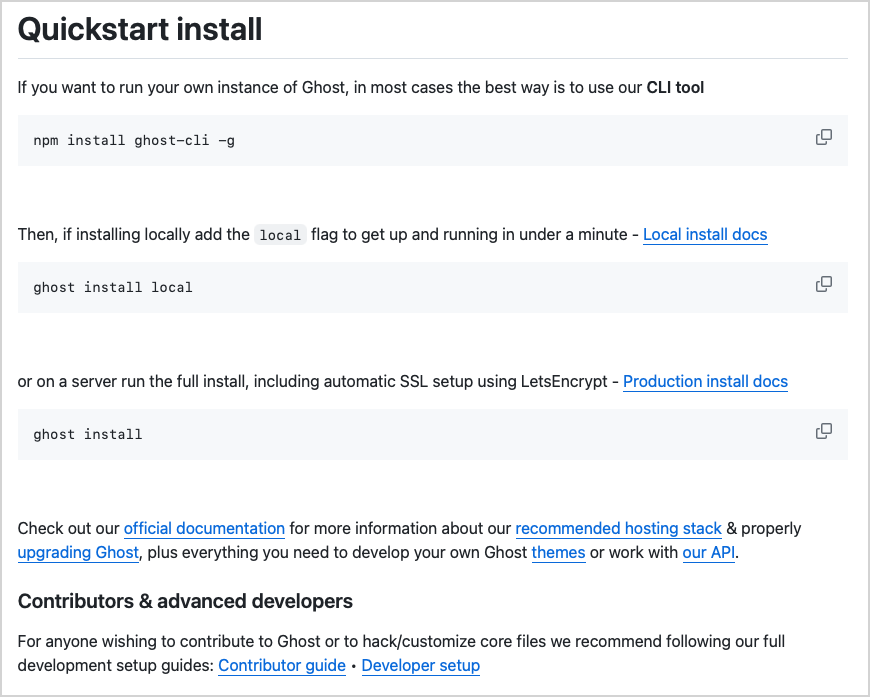

One of the strongest reasons to move to Ghost is that it’s built on top of open source software. The names are a bit confusing; there are several things people mean when they say “Ghost”:

- The open source project Ghost, which is a framework for “modern publishing”. It supports blogging, newsletters, and managing free and paid content. Because the core framework is open source, you can either self-host your publication or use a managed service.

- The managed hosting service Ghost Pro.

- The non-profit organization Ghost, which operates the Ghost Pro managed service. Revenue from operating the managed service supports ongoing development of the open source framework.

I’m going to use the managed version, because I want to focus on writing without having to do a bunch of sysadmin work. Because of its basis in open source, I feel much more confident that Ghost will be a long-term home for Mostly Python than I ever felt with Substack.

At this point it’s hard to choose a closed platform if an equivalent platform is available that’s built on open source. I’ve watched so many closed platforms and services take one or more of the following paths:

- Introduce ads in an effort to monetize user-generated content;

- Adopt dark patterns that pull users into higher usage levels than they originally intended;

- Add features that aren’t aligned with the original purpose of the platform or service, and slowly push people into using those features;

- Close off features and services that were central to the original platform’s appeal.

If Ghost Pro happens to fall into any of these patterns, there are two possibilities other than just moving to an entirely different platform. Since Ghost itself is open source, anyone can build a competing hosting service that leaves out the problematic features. Migrating between platforms that use the same underlying framework is much easier than migrating between different proprietary platforms. If a reasonable managed service doesn’t appear, I can always choose to self-host the service. I don’t particularly want to do that, but I may choose that option over migrating yet again Again, I don’t think I’ll need to move off of Ghost because it’s not susceptible to the same kinds of pressures that Substack is.2

The bigger picture

Most people reading this post probably aren’t planning to start a newsletter anytime soon. But many people are making decisions on a regular basis about which services to pay for, and which service providers to trust. When you’re working through these kinds of decisions, consider each of the following questions:

Can you export your critical data?

I knew Substack might not be a long term fit, but I was willing to give it a try because they allow you to export all your critical data. Writers “own” their content and subscriber list, and can export those at any time. Platforms that support exporting, and allow you to retain full ownership of your data, make it easy to implement effective backup routines and give you a way out of vendor lock-in.

Make sure you run an export early on, and look at exactly what’s in that export. While “you own your data and you can leave at any time” sounds nice, it’s probably a lot of work to process that data in a way that it can be used on another platform. Also, platforms don’t always keep their export services fully up to date. You might rely on a platform’s export function, and then when it comes time to use that data (for backup or migration purposes), find that some critical elements were never included in the export.

What’s the platform’s business model?

Every platform and service costs money to run. If the platform is charging enough for its core services, it’s more likely that they’ll be able to continue offering those services without trying to push unwanted “features” on the user base.3

How have they funded operations so far?

Understanding a platform’s funding history can give you a sense of how reliable their service is likely to be. For example, Substack has raised on the order of $100 million in venture capital. Now they need to generate enough revenue to pay that original investment back, while covering current operating expenses, and making a profit on top of that. If they can’t do that, they’ll need to seek even more funding, get acquired by a larger company, or fold. Sometimes a company will drift from its original mission in pursuit of a business model that’s profitable enough to pay off their earlier investment rounds.

The fact that a company has sought venture funding is not a bad thing in and of itself. It’s one way that promising companies can grow quickly, while they’re still establishing sustainable revenue streams. If funding levels align with a valid business model, the company may become sustainable. If a company has grown rapidly without a clearly sustainable business model however, that company’s platform can be much less reliable in the long term.

If you’ll only need a company’s services for a short time, none of this matters too much. But if you’re planning to rely on a service over a period of years, considering these kinds of details can help you make an informed decision about which platforms to trust.

What’s the public perception of the company?

In some areas, public perception doesn’t mean a whole lot. Nobody really likes Oracle, but that company is probably going to be around for a long time. People have serious frustrations with Adobe’s subscription plans, but their services are pretty reliable if you choose to use them.

A platform that requires a large user base, who could leave at any time, is a much different story. Platforms collapse and get acquired on a regular basis. Sometimes that plays out as a company closing suddenly, and sometimes the company does things over time that drive more and more users away. If the platform you’re choosing is susceptible to these dynamics, look at some of the public statements its leaders are making. Try to get a sense of whether they might be creating problems for themselves in the near to mid term future, or if they inspire confidence in their leadership and decision-making abilities.

Every time Substack has experienced conflict around their policies, they’ve doubled down on the policies that led to those conflicts in the first place. I’ve spent a good part of my life dealing with conflict, and I’m happy to address it when necessary. But when a company or platform fosters conflict because it increases engagement, I want no part of that.

Conclusions

I’ve really enjoyed writing Mostly Python over the past year, and look forward to many years of continuing to do so. Next Thursday’s post will have the same kind of content you’re used to seeing here; it will just look a little different.

I’ll send one last email out from Substack after publishing from Ghost for the first time. That email will include a way to reach out if something goes wrong in the transition. If you’re a paid subscriber, Substack and Ghost both use Stripe for billing, so your subscription should carry over smoothly.

Thank you for joining me here on Substack, and I hope you’ll stay with me through this transition as well.

What started as a simple newsletter delivery platform is turning into a haphazardly built social media site. Last year Substack introduced Notes, its Twitter clone. They said they were building Notes without moderation, because they trust users to moderate themselves. Last fall Substack was called out quite publicly for allowing literal Nazi content on their platform. When they finally responded to an open letter from Substack writers, they basically said they don’t like Nazis but believe that any level of moderation equates to censorship. This free-speech absolutism is disingenuous; every public communication platform has to deal with moderation. If you’re interested in more specific thoughts on all of this, I wrote a more detailed overview of Substack’s issues previously.

Substack continues to build “features” that are aimed at simply inflating everyone’s subscriber numbers and connectedness on the platform. They’re starting to adopt dark patterns that lead people to subscribe to more newsletters than they intend to, and follow more people on Notes than they intended to as well. If you’ve been around the internet for a while, you’ve seen this play out before. What starts as a clean platform develops into one with more and more calls to “engage” and less of a focus on actual content. ↩

If you happen to be considering self-hosting Ghost for one of your projects, Molly White wrote a fantastically detailed post about her initial setup. ↩

Substack’s main revenue source is that it keeps 10% of all revenue from paid subscriptions. That means they’re under constant pressure to increase the number of paid subscriptions, and the amount that people are paying for those subscriptions. Ghost, and most other newsletter platforms, charge volume-based usage fees. That means those platforms can let individual writers choose how and when to prompt readers to consider a paid subscription.

It’s much easier to avoid the temptation to implement dark patterns if you have a sustainable business model in the first place. ↩