Debugging in Python, part 12: Using an IDE's debugger

MP 155: Using an IDE debugger to understand a program's internal behavior.

Note: This post is part of an ongoing series about debugging in Python. The posts in this series will only be available to paid subscribers for the first 6 weeks. After that they will be available to everyone. Thank you to everyone who supports my ongoing work on Mostly Python.

In the last post, we started implementing the game play for Go Fish. We were working on managing the player's turn, and things were working well in some play-throughs. However, there were some play sequences that demonstrated buggy behavior. In this post we'll use an IDE's interactive debugger to get to the root of that problematic behavior.

A repeatable bug, even when using random

At the end of the last post I showed a couple examples of incorrect behavior when managing the player's first turn. All the examples I've come up with involve the behavior after an invalid guess is handled correctly.

Debugging logic that involves randomness can be difficult, because it can be hard to consistently generate the same buggy conditions. One strategy for addressing this is to give the random number generator a seed, so you can generate repeatable output.

Starting with the most recent version of the Go Fish code, let's add a random seed to the game so we can work with deterministic output:

class GoFish: def __init__(self): # Start with a new shuffled deck. random.seed(42) self.deck = Deck() self.deck.shuffle()

If you're following along, make sure you import random into this file as well.

Let's try to create a bug. I'm going to make a valid guess, followed by an invalid guess, and then one more valid guess. I'm pretty sure that will demonstrate the buggy behavior we need to address:

$ python go_fish.py -v Player hand: 2♥ 3♦ 3♥ 5♦ 6♥ 8♣ Q♠ Computer hand: 2♦ 3♣ 4♠ 5♣ 10♦ J♥ K♣ What card would you like to ask for? 2 Your guess was correct! Press Enter to continue. Player hand: 3♦ 3♥ 5♦ 6♥ 8♣ Q♠ Computer hand: 3♣ 4♠ 5♣ 10♦ J♥ K♣ What card would you like to ask for? b Invalid entry, please try again. What card would you like to ask for? 3 You don't have that card! What card would you like to ask for? 5 $

This is definitely buggy behavior. I first guessed a 2, and it was evaluated as a correct guess. It was processed correctly as well; both hands had a 2 removed, and both players are down to six cards. I then guessed a b, which isn't a valid card. It was correctly identified as an Invalid entry.

That's when the buggy behavior starts. I guessed a 3, which I definitely have, and the game tells me You don't have that card. I then ask for a 5, which I also have, and the game just ends. It doesn't crash, it doesn't report any issues, it just ends silently.

Before moving on, I wanted to make sure I can repeat the exact same guesses, and see exactly the same output. I won't repeat the output here because it's identical to the listing just shown. That's really satisfying, because if we find a fix for this bug, we can use the random seed 42 to start with the exact same game conditions, and verify that our fix works for this specific bug. This is incredibly helpful in both manual and automated testing.

Debugging with an IDE

We could keep using pdb, and it's usually what I reach for first when starting a debugging session. But we've already looked at that, and sometimes it's nice to use something more visual. For this bug, let's use an IDE's debugger. I use VS Codium, the open source core of VS Code, but many IDEs have similar built-in debugging features.

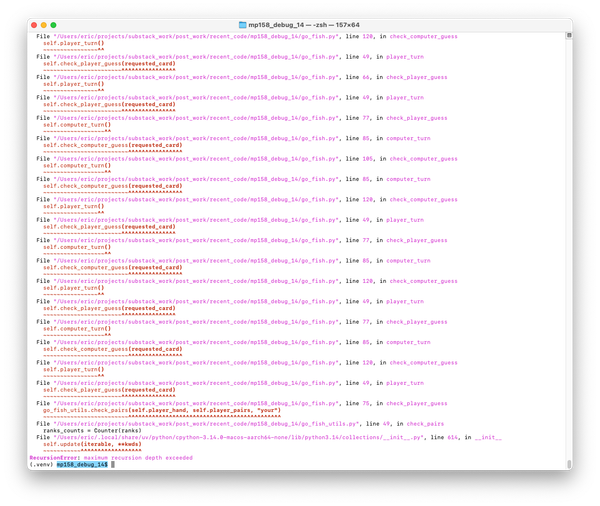

To start a debugging session in VS Codium, open your project's main file, in this case go_fish.py. Then click Run > Start Debugging. You get a sidebar with sections labeled Variables, Watch, Call Stack, and Breakpoints. Instead of having to type breakpoint() into your program file, you can click next to a line number and the IDE will insert a breakpoint, indicated by a red dot. This breakpoint is managed by the IDE; if you run the program in an external terminal, the breakpoint won't exist.

Here I've set a breakpoint at the start of check_player_guess(), because that's where I want to start watching the program's behavior:

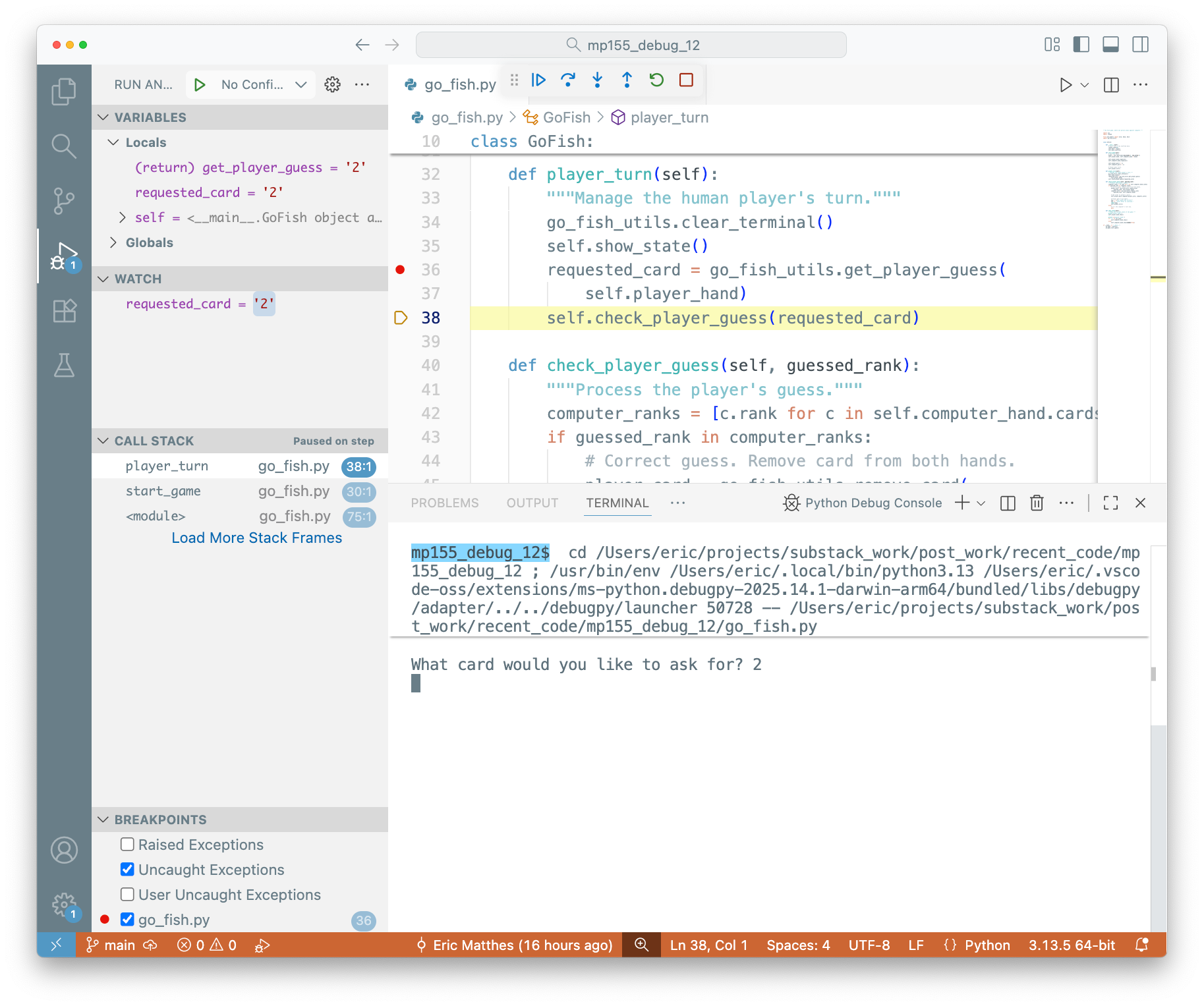

breakpoint() directly into the code.To see the debugger in action, enter a guess. Execution stops at the breakpoint:

This is just like the breakpoint you set manually using pdb. But instead of waiting for you to enter the names of variables you want to inspect, they're all available in the Variables pane in the sidebar. Here we can see that the value of guessed_rank is 2. We can also see, for example, that both player_pairs and computer_pairs are still empty lists. You can click on the player_hand dropdown, and see all the cards in the player's hand.

All this information is available in a pdb session, but you have to inspect variables through the command line. That's helpful for a lot of bugs, but for more subtle bugs and more complex logical flows, being able to point and click can be much faster and more efficient.

To continue execution, you use the navigation buttons at the top of the VS Codium window:

You can continue execution until the next breakpoint is hit (triangle), step over the next function (curved arrow), step into a function (down arrow), and step out of a function (up arrow), and stop execution (red square). If you're not sure which to choose, stepping forward with the down arrow is a safe choice, because you'll go one step at a time. When you've seen enough, you can click Continue to move ahead to the next breakpoint.

I clicked the down arrow and watched the 2 be identified as a correct guess. I watched it be removed from both the player's hand and the computer's hand, and then saw that those cards were added to player_pairs.

That was enough to see that things were working correctly for the guess of 2.

Watching a variable

There's a bunch of information available in the Variables pane. There can easily be too much information to watch in that pane, especially as you move through your program's logical flow.

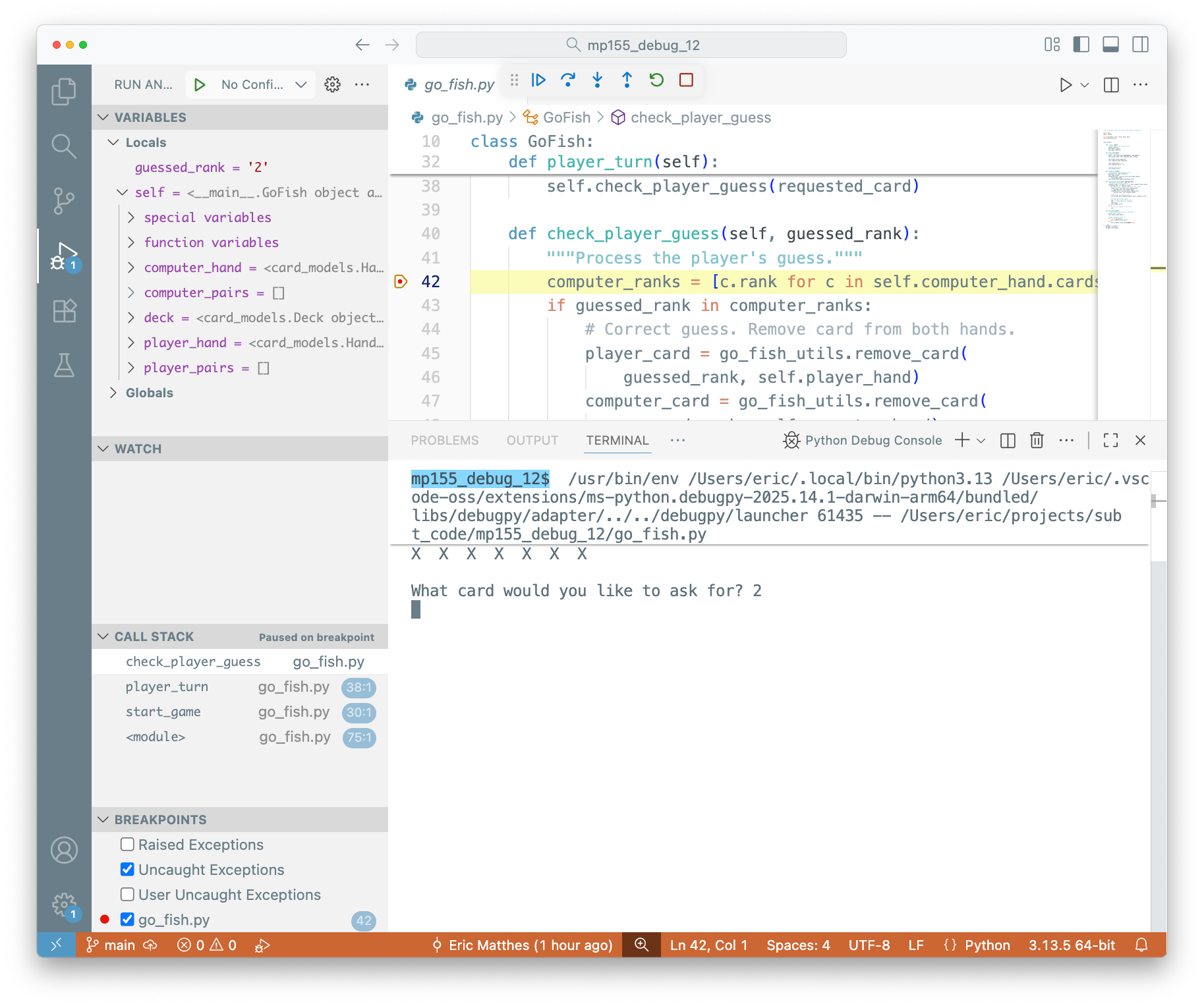

When you know which variables you want to watch closely, you can add them to the Watch pane. I added guessed_rank to the Watch pane, because I was suspicious that this value might not be correct in certain conditions.

The value associated with guessed_rank is only available when execution is inside check_player_guess(). When you watch a local variable like this, you'll see its value as undefined whenever execution leaves the function. But as soon as execution comes back to that function, you'll see its value again. This is really helpful as you hop around your program's logical flow.

I pressed Continue, so I could enter the invalid guess of b, while watching the value of guessed_rank.

A stale value?

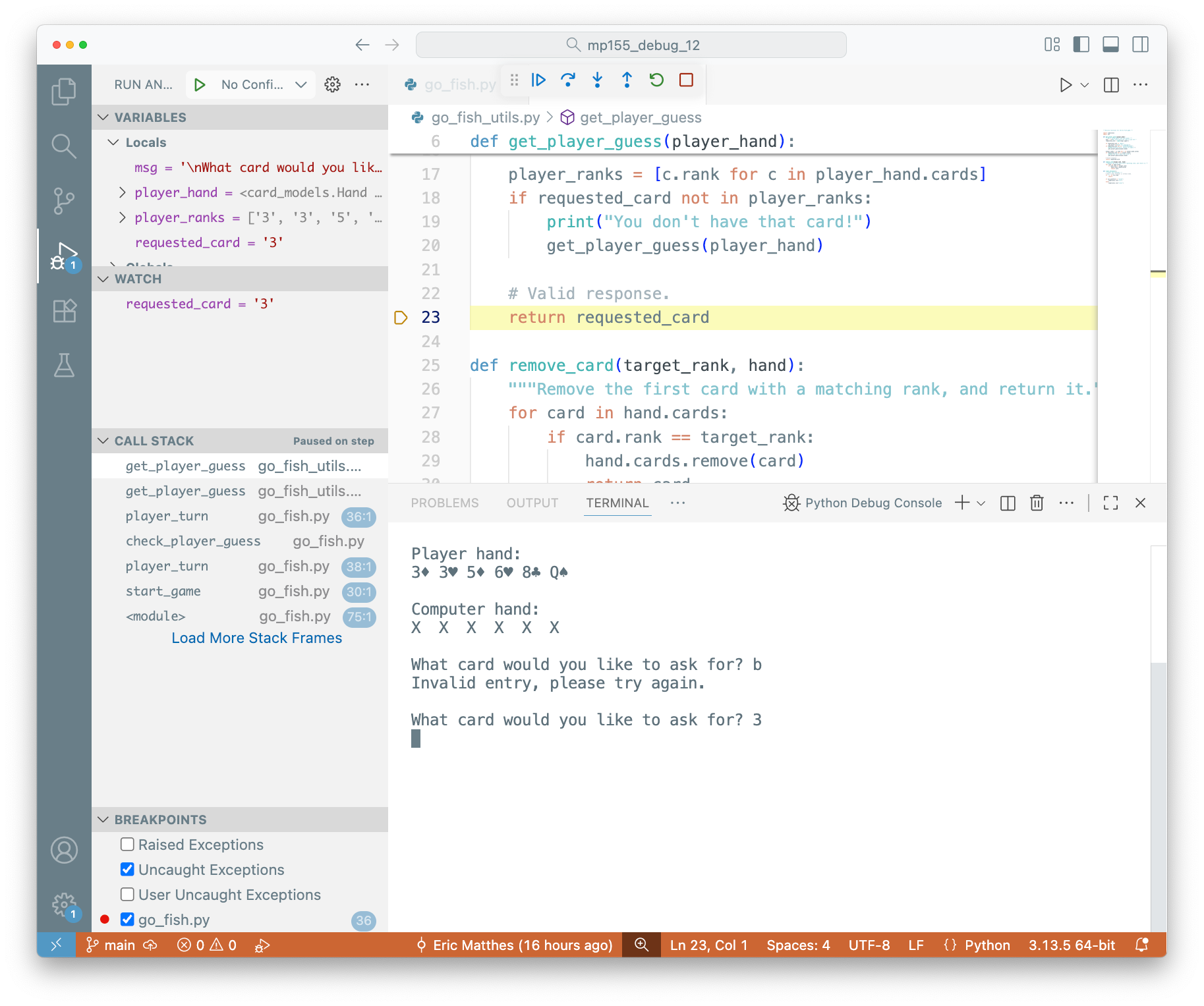

I entered b for my second guess, and it didn't hit the breakpoint. It's an invalid guess, so it never reaches check_player_guess(). I entered 3, and execution still didn't hit the breakpoint. The 3 was (incorrectly) considered invalid. Here I made a note to set a breakpoint in the code that validates guesses, because I want to see exactly why that 3 is rejected.

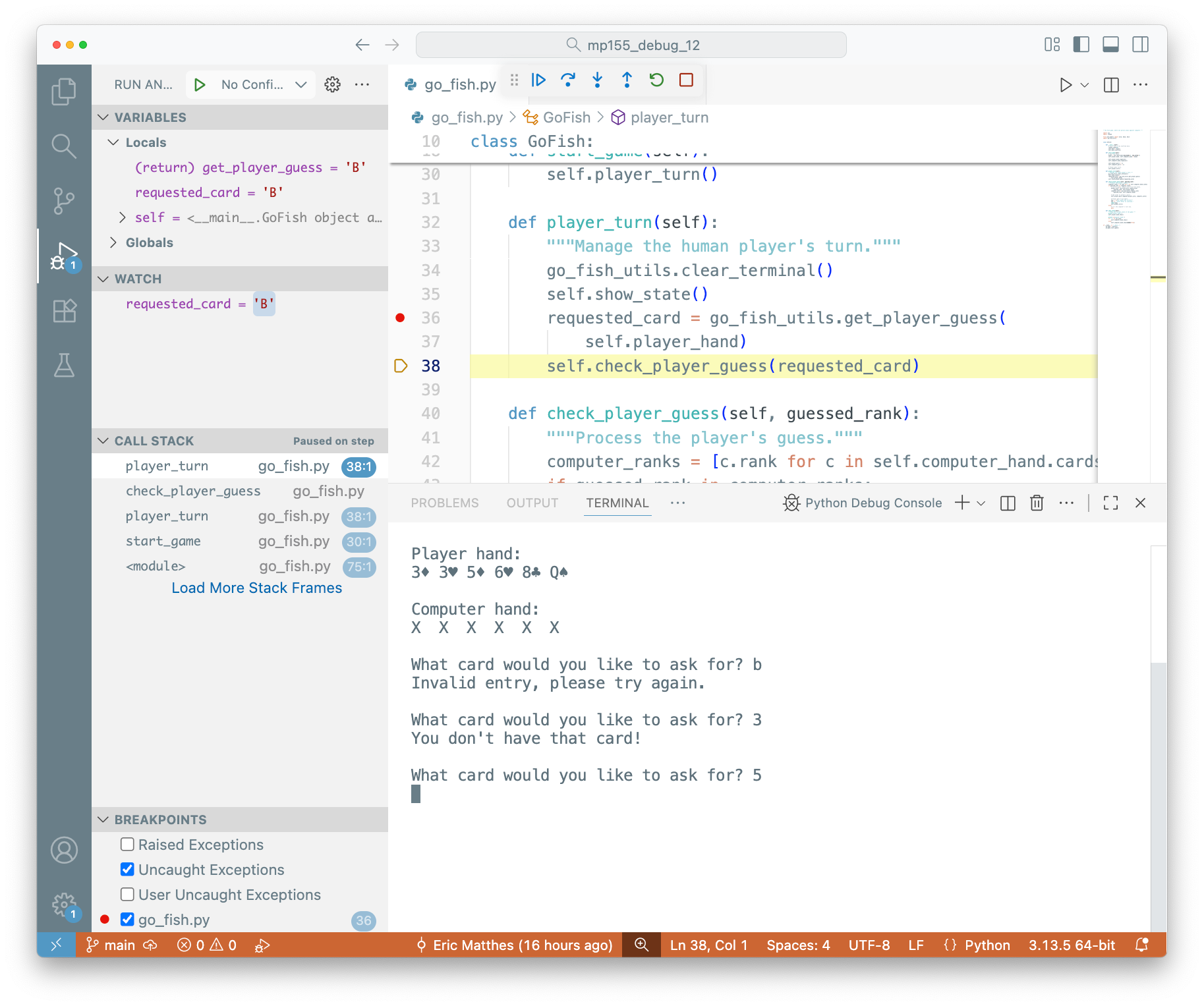

I guessed a 5, and saw the following logical state:

5, and execution has reached check_player_guess(), but the value of guessed_rank is B.I just entered a guess of 5. I hit the breakpoint in check_player_guess(), which means the 5 was considered a valid guess. But here in check_player_guess(), the value of guessed_rank is B!

A spark of understanding

One of the challenges of teaching debugging is that every debugging session involves a spark of insight, where you start to understand what might be going wrong. The whole goal of teaching debugging techniques is to help people find their way to these moments of insight about their program's logic.

For me, I felt that moment of insight right here. The B is a stale value; that guess should have disappeared after it was deemed invalid. There shouldn't be any way we can see a B again. I have a couple suspicions about why this might be happening. One is that guesses are somehow being kept in memory after they're determined to be invalid. My other suspicion, which is probably related, is that I'm not returning values correctly from a method like check_player_guess(), or a helper function like get_player_guess().

Another play-through

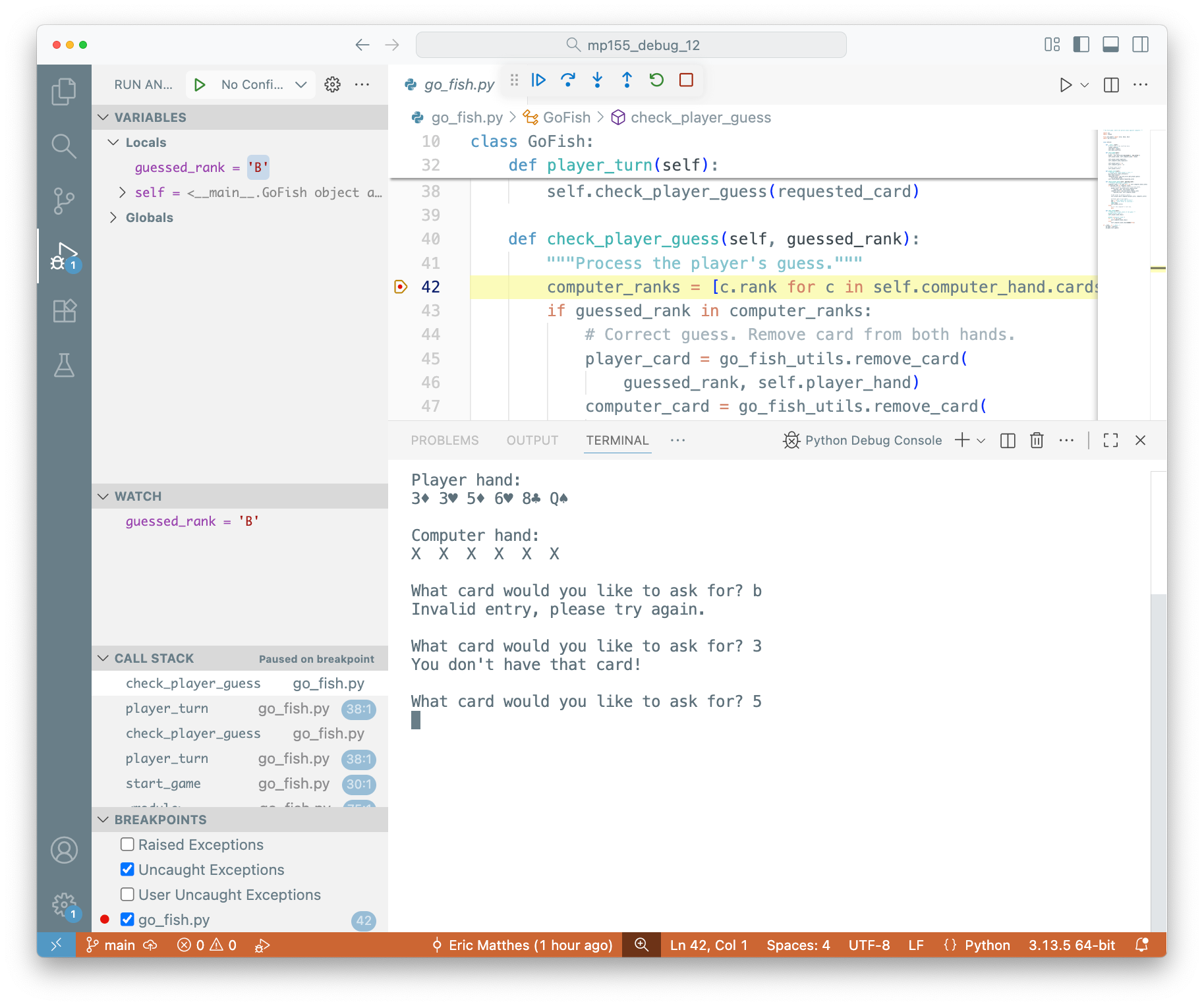

I want to do one more play through of the same guesses, but this time I want to watch what happens with requested_card in player_turn(). I set a breakpoint at line 36 in go_fish.py, and made the first guess. The value returned to requested_card was 2, as expected:

player_turn(), so I can watch how a guess is assigned to requested_card.I stepped through each line until the value for requested_card was returned, and it was a 2. All good so far. I then clicked Continue, to move ahead to the next guess.

I asked for a b, and it was rejected within get_player_guess(). An invalid guess calls get_player_guess() again, and I asked for a 3 this time.

Here's where it got interesting. The guess of 3 passed all the validation checks, and execution jumped to the line where get_player_guess() should return the valid guess:

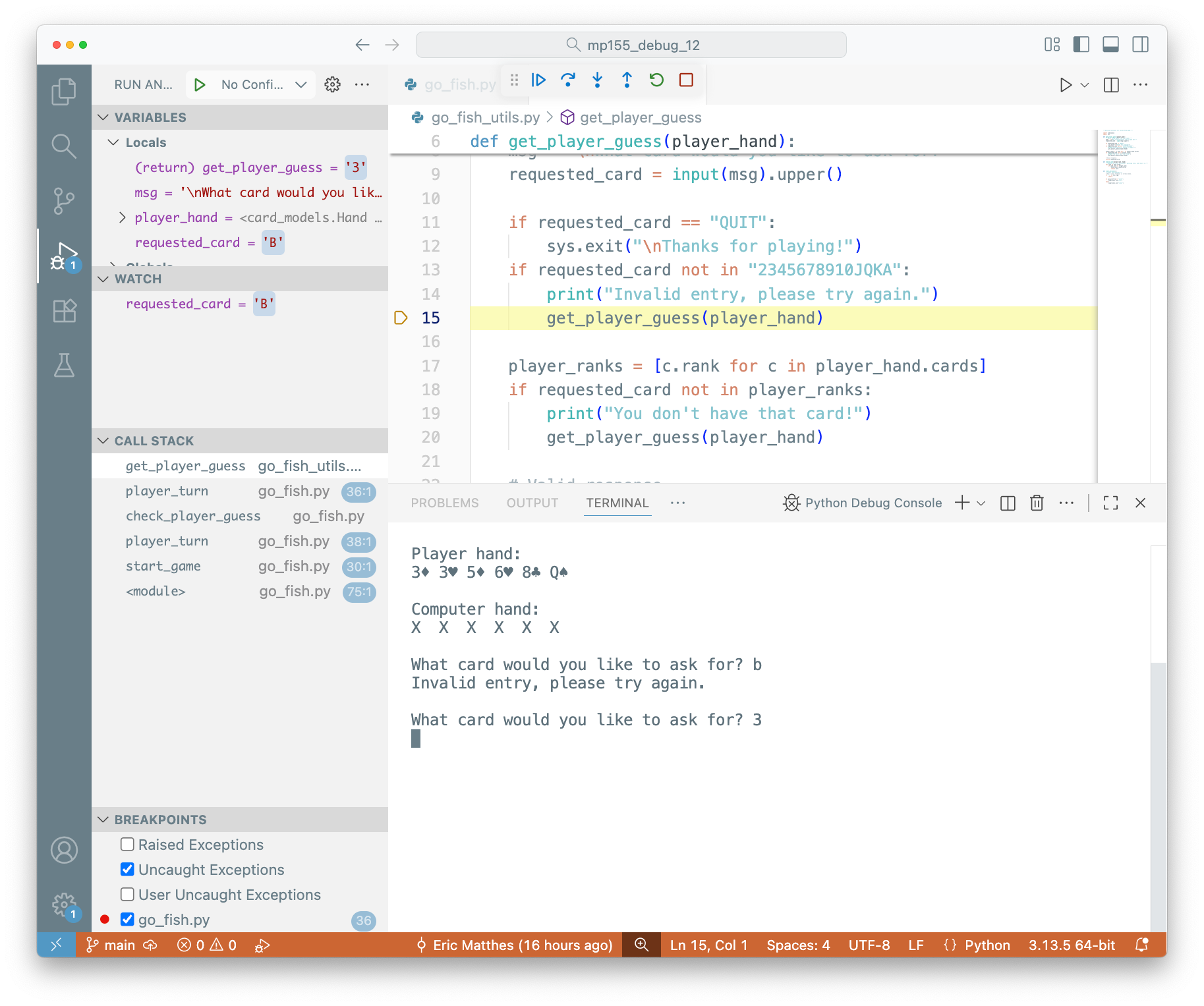

3 has passed all validation checks, and is about to be returned by get_player_guess().However, instead of returning the 3 to player_turn(), execution goes back to get_player_guess(). More surprisingly, the value of requested_card is now B!

player_turn(), we're back in get_player_guess()!The B fails validation, which starts get_player_guess() all over again.

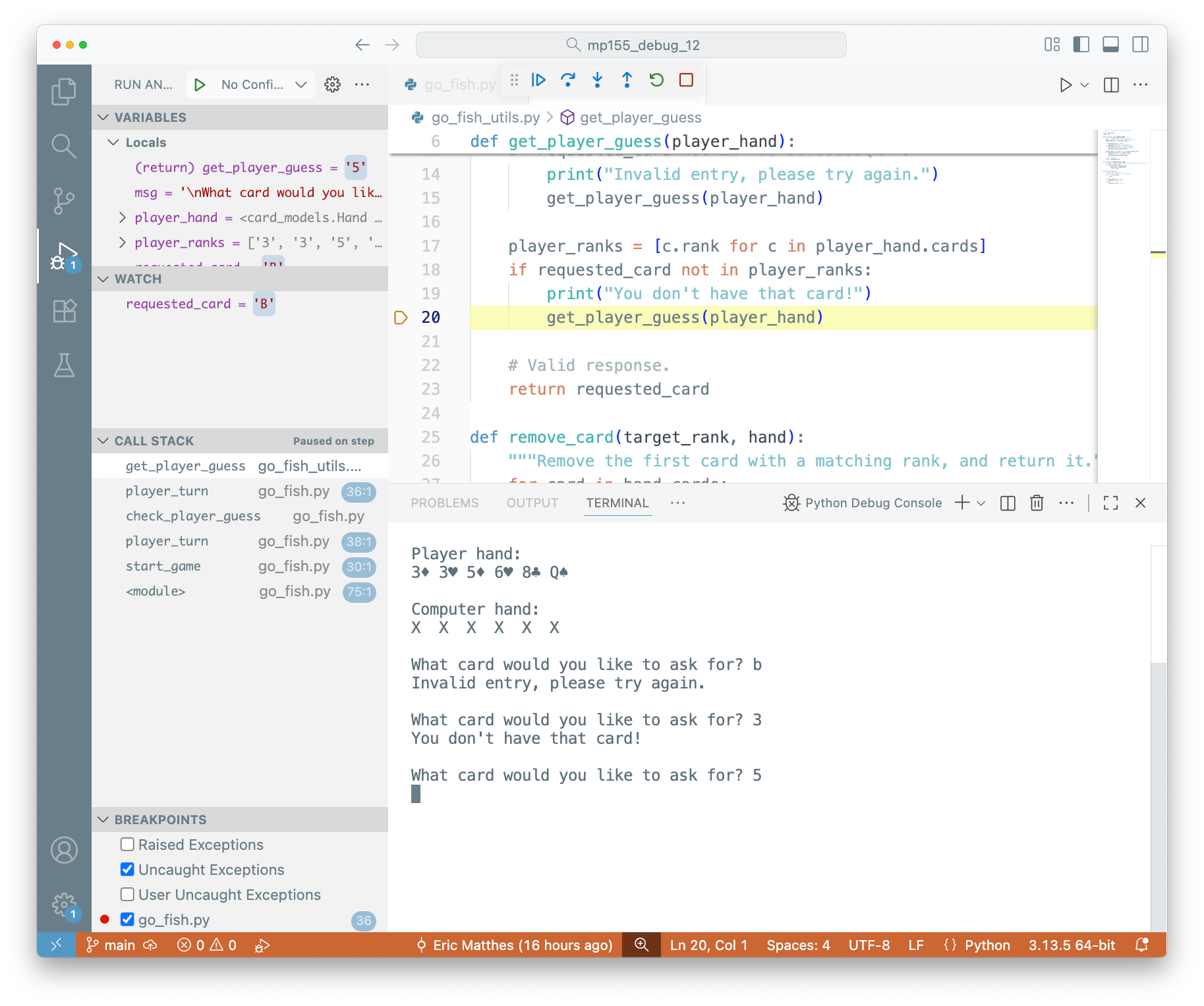

I guessed a 5 this time, and that guess passed all the validation checks. But execution goes back to get_player_guess() one more time, and the value of requested_card is B again!

5, the value of requested_card is still B.Stepping through a few more times finally returns execution to player_turn(), but the value that's returned from get_player_guess() is B:

player_turn(), but the returned value is B.We guessed b, then 3, then 5, and we got a B from get_player_guess().

What's going on?

Let's summarize what's happened in the game so far. We first guessed a 2, which was in both hands, and it was handled correctly. We then guessed a b, which was correctly rejected as an invalid guess. We then guessed a 3, which should have been valid, but was rejected because the guess that was actually processed was a B. We then guessed a 5, which passed all validation checks. But instead of returning the 5, get_player_guess() returned a B.

If you're not clear at this point about what's happening, consider downloading the project at this point and running your own diagnostics. It's a pretty interesting real-world debugging situation.

A subtlety of recursion

To understand the issue, let's look at the full get_player_guess() function:

def get_player_guess(player_hand): """Get a valid guess from the player.""" msg = "\nWhat card would you like to ask for? " requested_card = input(msg).upper() if requested_card == "QUIT": sys.exit("\nThanks for playing!") if requested_card not in "2345678910JQKA": print("Invalid entry, please try again.") get_player_guess(player_hand) player_ranks = [c.rank for c in player_hand.cards] if requested_card not in player_ranks: print("You don't have that card!") get_player_guess(player_hand) # Valid response. return requested_card

This is a recursive function. It calls itself if the player's guess is not a valid card, or if the player isn't holding the guessed card. The logic is mostly working; we've shown that the function does call itself in both of these logical paths.

When you use recursion though, each call to the function needs to return the value that's generated. Otherwise a stale value can be returned after multiple passes through the function.

The fix?

We should be able to fix this by adding a return in each line that calls get_player_guess(). That should pass the most recent guess back through the execution flow, and return it to player_turn().

Here's the proposed fix:

def get_player_guess(player_hand): """Get a valid guess from the player.""" msg = "\nWhat card would you like to ask for? " requested_card = input(msg).upper() if requested_card == "QUIT": sys.exit("\nThanks for playing!") if requested_card not in "2345678910JQKA": print("Invalid entry, please try again.") return get_player_guess(player_hand) player_ranks = [c.rank for c in player_hand.cards] if requested_card not in player_ranks: print("You don't have that card!") return get_player_guess(player_hand) # Valid response. return requested_card

Here's another clear demonstration of how helpful the random seed is. We have a proposed fix, and we get to see if it resolves the exact bug we reproduced earlier. Let's see if it does:

$ python go_fish.py -v Player hand: 2♥ 3♦ 3♥ 5♦ 6♥ 8♣ Q♠ Computer hand: 2♦ 3♣ 4♠ 5♣ 10♦ J♥ K♣ What card would you like to ask for? 2 Your guess was correct! Press Enter to continue. Player hand: 3♦ 3♥ 5♦ 6♥ 8♣ Q♠ Computer hand: 3♣ 4♠ 5♣ 10♦ J♥ K♣ What card would you like to ask for? b Invalid entry, please try again. What card would you like to ask for? 3 Your guess was correct! Press Enter to continue. Player hand: 3♥ 5♦ 6♥ 8♣ Q♠ Computer hand: 4♠ 5♣ 10♦ J♥ K♣ What card would you like to ask for? 5 Your guess was correct! Press Enter to continue. Player hand: 3♥ 6♥ 8♣ Q♠ Computer hand: 4♠ 10♦ J♥ K♣

This seems to have worked. Every guess is handled correctly. The 2 is identified as correct, and it's processed correctly. The b is identified as invalid, and then the 3 is identified as valid and correct, and it's processed correctly. Finally, the 5 is identified as correct, and is processed correctly as well.

Conclusions

There are a couple takeaways here. First, using an IDE's debugger can be much more helpful than just using a pdb session in a terminal. If you've never explored your IDE's debugging tools, give them a spin and see how much information they put at your fingertips. I encourage you to become comfortable using both, and reach for whatever seems like it will be most efficient in the situation you're facing.

Print debugging is useful sometimes. For example if you just want to see if a function is hit under specific conditions, adding print("HERE") can be a quick and easy way to check. But avoid the habit of adding print() calls throughout your code just to see the value of a bunch of variables. Both pdb and IDE debuggers are much better for that kind of work.

Last, keeping track of your program's logical flow is not always easy. We develop a mental model of our program as we work on its codebase, and most of the time our mental model matches what the program does. But there are many ways for our mental model to diverge from what the program actually does. Learning to inspect logical flow takes practice. Fixing bugs requires leaps of intuition, and you set yourself up to make those leaps when you can inspect your project's logical flow in a variety of ways.

In the next post we'll check to see if there are any obvious bugs remaining, and try to finish the Go Fish game.